There are many kinds of borders. Some of them caused friction in the Midwest during the pandemic.

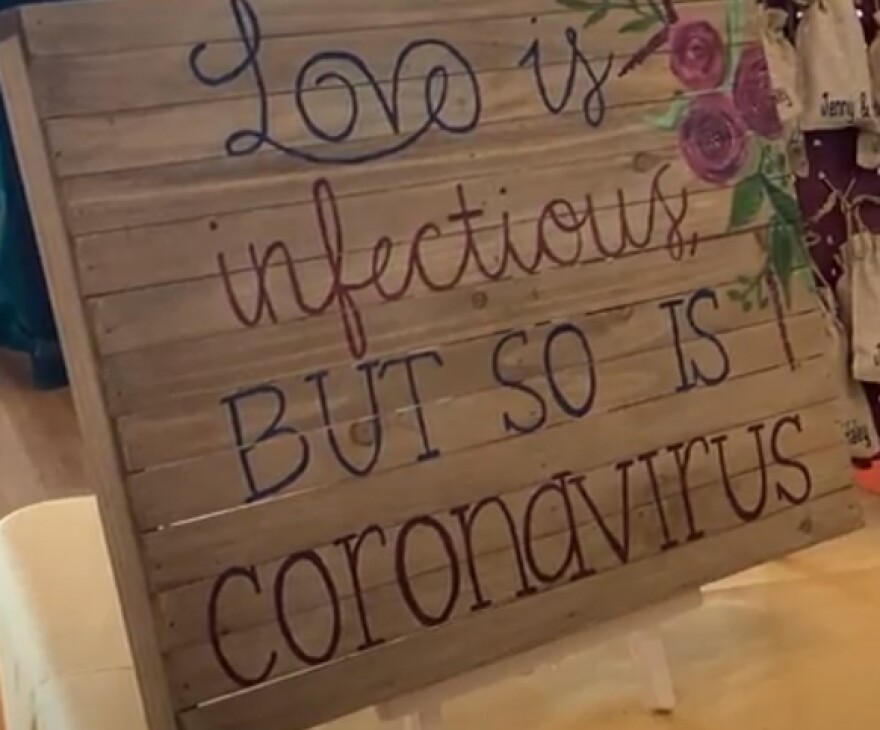

On a Friday in September, Haley Edlin and Jenny Hockenberry were tying the knot in front of their family and friends in Louisville, Kentucky.

After years of sharing mutual friends and some on-again, off-again dating, the couple finally settled into a home, started a family, and planned a wedding.

But the timing wasn’t exactly right if you consider the global pandemic. While some normalcy has returned to Kentucky, with businesses reopened and gatherings allowed, COVID-19 was at its height this fall. Cases began to rise in July and haven’t slowed.

Hockenberry and Edlin had hoped for a wedding date in September to mark one year since the couple proposed to each other on the same day in 2019.

The couple chose the date confidently at the end of 2019. Even as Kentucky hunkered down in March, Hockenberry thought the height of the pandemic would be over by September; it would have to be.

“Right. I guess everybody kind of thought that,” Hockenberry says.

Eventually, she realized it wouldn’t be better before her wedding in September. There were some options on the table: postponing or eloping. Neither felt right.

“Both of us pretty much didn't enjoy planning a wedding as it was. And so we did not want to postpone,” Hockenberry says.

So the couple decided to keep the date. They asked all guests to wear masks at the ceremony and opted for outdoor seating for the reception.

They even scaled down their guest list, which was a bit awkward since they already had sent save-the-date notices earlier in the year.

But then they sent out an ‘uninvitation’..."or we call it, ‘you're on the B-list’,” Hockenberry says.

But even for the guests Hockenberry was expecting, the A-listers, some weren’t able to make the trip.

Chicago’s Mayor Lori Lightfoot issued an order in July that restricted travel to “hot spot” states, places where COVID-19 was surging. Cook County public officials soon adopted the same standards. That would affect bride Hockenberry’s closest family: her parents living in a Chicago suburb and her brother in the city.

However, Kentucky wasn’t on that list of hot spot states in July or August. But September brought Kentucky’s positivity rate up to 10 percent. And Chicago took notice. Just one week before the wedding, Kentucky made the hot list.

“If my parents weren't able to come, if my brother wasn't able to come, that would probably lead us to a discussion of ‘Are we going to still really do this?’,” Hockenberry says.

Despite the challenges, her parents made it.

“There was never a time when I thought I wouldn't come down for the wedding,” Jenny’s mother, Judy Hockenberry says. “We always had it in our mind that there was nothing...come hell or high water, we were going to see our daughter married.”

Even Hockenberry’s grandparents, who are in their eighties, came down from the Chicago area. Her grandparents are more at-risk because of their ages, and the stakes seemed high.

“I was very clear with my grandparents about ‘you all do not have to do this, and it will be okay',” Hockenberry says. “[but] I'm the first grandchild to get married, and they're getting up there.”

Hockenberry’s aunt Karen Seunarine even flew in from Canada. She would have brought her whole family with her, four kids and her husband, but the border is closed for ground travel.

After the ceremony, as everyone headed outdoors for dancing and drinks, Seunarine wanted to share something on her phone. It was a photo from her son sitting in front of his TV, streaming the ceremony, and decked out in a tux.

Two States at Odds

Kentucky and Indiana are separated by the Ohio River. During the pandemic, this waterway has come to signify two different paths regarding COVID-19.

At the end of April, Indiana's death toll was three times that of Kentucky's. Despite those numbers, Republican Gov. Eric Holcomb chose May 1 to announce the reopening of Indiana retail and restaurants, to the shock of Kentucky’s Democractic governor, Andy Beshear.

Louisville business leaders called out how problematic the reopening plans were for Kentucky businesses who would lose revenue to restaurants and shops just across the river in Southern Indiana. Greater Louisville Inc. wrote to the governors, asking them to get on the same page.

Across the river, Wendy Dant Chesser is the director of One Southern Indiana Chamber of Commerce.

“We would have loved for a federal policy to come in and tell us all everybody's going to have the same guidelines,” she says.

But having worked in the bi-state area for decades, she admits she’s accustomed to juggling two sets of standards.

“We can't expect governor Holcomb to make decisions in Indiana, based on how it affects the Southern Indiana/Louisville market, when Gary, Indiana, is trying to figure out how to balance with what Chicago is doing. So from Indianapolis’s perspective, they have to do what's best for the whole state,” Dant-Chesser says.

Municipal and state public health officials are in the same tug of war. Sarah Moyer is the public health director for Louisville Metro.

She collaborates with public health officials across the river, but she hopes for systematic changes.

“Contact tracing is not anything new for us, but it's just always been done on a much smaller scale. Now, the problem is, it’s so massive. It's hard to keep up with collaboration when you have 14,000 cases in your jurisdiction,” she says. “I wish there was like a national public health registry database. So our systems in Indiana and Kentucky could talk to each other.”

A nation within a state

The pandemic has brought both conflict and collaboration to neighboring states. But even within a single state, political leaders can’t come up with a single vision.

COVID-19 has been politicized across the country, especially in the state of Wisconsin.

Democratic Gov. Tony Evers issued a stay-at-home order in late March. Within 50 days, state Republicans challenged his order, and the state Supreme Court overturned the mandate.

Republicans felt the order wasn't legal and made the case that each county should make its own rules. The rest of the state shouldn’t have to wait for urban areas like Milwaukee to cool down.

The back and forth over state COVID-19 restrictions hasn't affected all who live within Wisconsin, though. Within the tribal borders of the Oneida Nation, COVID-19 restrictions have been clear and undisputed.

“The messaging for our community has been consistent,” says Dr. Ravi Vir, chief medical officer for the Oneida Nation. About 7,500 tribal members live in nearby counties or on the reservation, which spans 65,000 acres in the Northeastern part of the state.

The sovereign nation had declared a public emergency and issued a stay-at home-order on March 12. Unlike the Wisconsin state order, this order stayed in place, granted with some revisions. In late July, a mask mandate was issued, and that’s still on the books as well.

Our challenge also is Native American communities have a lower life expectancy and have higher rates of health conditions like diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and high blood pressure than the general population,” Vir says.

Vir says the tribe’s autonomy has been critical for curbing the spread of the virus.

Despite that, the tribe’s caseload is actually higher than the state of Wisconsin's, proportionately. The tribal nation’s caseload is surging, right in line with its closest neighbors, Brown County and Outagamie County, which have about 26,000 cases together.

Wisconsin’s caseloads in October dwarfed anything the state had seen previously. The highest single day in July hit about 1,000 cases. By October daily counts were nearly three times that amount.

Native people in Wisconsin were hit hard. Wisconsin Public Radio reported that cases amongst Native Americans in the state tripled since the beginning of September. That report came out in late October.

Dr. Vir knows the tribal reservation is not an island.

“You can expand this further. What happens in Wisconsin affects our neighboring States, and what happens in our neighboring States affects Wisconsin,” he says. “And the more we can be consistently following those safety precautions, I think as a nation, as the United States, I think we're going to be in a much better place sooner rather than later.”

A once fluid Canadian border shuts down

The border has been closed to non-essential traffic since March. That is, America is welcoming travelers from Canada and most other countries, but Canada is closed off. On a monthly basis, the U.S. and Canada have renewed the closure. But if both countries are in their own second waves, something would drastically have to change to get the border open before the end of 2020.

The Canadian government hasn’t wavered on this stance, and neither have the people. Robin Levinson-King is an American reporting for the BBC out of Toronto.

“There's a recent poll in September from Research Co, and they found that about 90 percent of Canadians want the border to stay closed,” she says. “Most Canadians right now are worried. It's gonna get worse at home. It's going to get worse in the U.S.”

Those caught shirking the rules can face upward of half a million dollars in fines and months in jail.

“There was a man from Kentucky with Ohio plates, and he was traveling to Alaska. Americans are allowed to cross into Canada, but they're supposed to take the most direct route, and they're not supposed to sightsee on their way. This man was ostensibly going to visit Alaska, but he was caught sightseeing in Provincial Park,” Levinson-King says. He faced a fine of more than $500,000.

Compare that to the U.S. where quarantine measures seem largely unenforceable.

Levinson-King’s reporting shows that about 300,000 people crossed the U.S.-Canada border on a daily basis before the pandemic. But in March of 2020, non-commercial land border traffic was just five percent of what it was before.

“So there's typically twice as many highway travelers (non-commercial, roadtrippers) than flights and commercial truck travel combined. So it really is those communities along the border that used to get people crossing and shopping and visiting that are hurt the most,” she says.

These would be tourism towns that rely on American visitors. Levinson-King mentioned Niagara Falls as an example.

Another would be border towns that essentially share residents, workers and consumers.

“Windsor, Ontario, which is right across the border from Detroit, these two cities were kind of like sister cities,” Levinson-King says. “People would live in one city and work in the other, and they would cross the border daily. It was really a very fluid situation. And I think now it's kind of like having an arm chopped off."

These sorts of towns are so intertwined that people might have significant others on the other side and might not have seen that as a long-distance relationship, until COVID-19. The Detroit Free Press interviewed a young, engaged couple; one lived in Windsor and the other in a suburb of Detroit. If they were married, the travel would be permitted.

That couple and other families have made pleas to the Candadian government. And public leaders took note. In October familial exceptions were made for some, such as siblings and grandparents, including those who’ve dated for a year or longer. “Compassionate visits” are allowed for extended family and friends to see a loved one in their last days or for a funeral.

Canada is requiring strict quarantine measures and written approval from federal agencies. It also sent almost 200 health officials to the border.

Home for the holidays?

Lis Wang is British-Canadian, but she’s been living in Grand Rapids, Michigan, with her husband.

It was a welcome change, since she ended up only a five-hour road trip away from Calargy, Alberta. She was born there and considers it home.

“It's definitely a place I'm missing a lot these days,” she says.

Her parents and extended family still live there, including her brother and five-year-old niece.

“I've been away for so many years, like building a relationship with my niece has been tough, and then not being able to be home to see her has been also very tough,” says Wang.

She was used to visiting every few months and staying for long stretches. Even in London she made the trip twice a year.

Now, plans have already been canceled.

“One of my aunts...was having her 88th birthday in Vancouver back in April [and] 88 for a Chinese granny is quite an important date. The plan was everyone around the world--from China, from Calgary, from the U.S.--would fly to Vancouver and throw this giant party for her,” Wang says.

That didn’t happen. Wang missed Thanksgiving. And now she is wondering about Christmas.

“That is up for debate on a daily basis,” she says. “We don't think we're gonna make a decision until December; it's going to be one of those really last minute things just because you don't know what can happen over the next two and a half months, because it's hard to anticipate anything this year, right?”