In Episode Five, we reveal how Midwestern COVID-19 data gathered by University of Evansville data scientists led us to some of the stories in this series.

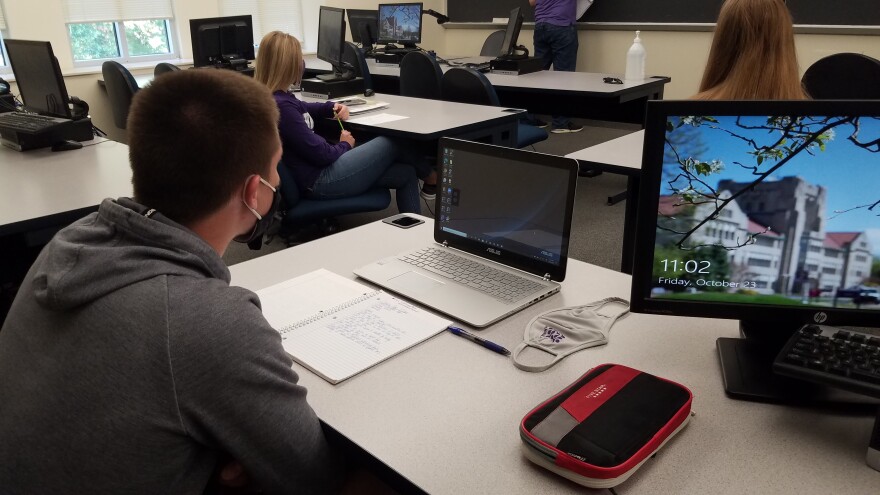

Dr. Darrin Weber and his fall semester ChangeLab class students, Maya Frederick, Timmy Miller, Ethan Morlock and Pearl Muensterman created an extensive data visualization of the coronavirus progression in our seven state project area.

Before we go any further in our reporting on COVID-19 in the Midwest, we’re going to tell you where these stories come from, how we found them and why our process makes this series unlike anything else being done on the pandemic. How did we know where to look? How did we keep from just re-telling different versions of the same news? Well, we got help from data expert Dr. Darrin Weber and his team of University of Evansville students.

The data that is out there for Covid in the Midwest is a mess. The largely hands-off approach of the federal government left state and local governments with no set standard of data gathering. Everywhere was reporting things a little differently.

Our goal with Covid Between the Coasts is to accurately and authentically report on the impact of the pandemic in seven Midwestern states. We needed our own data scientists. Experts who could do the meticulous, skilled work of cleaning data and helping us communicate its meaning.

University of Evansville mathematics professor Dr. Darrin Weber and four of his students spent countless hours over seven months to guide us to some of the stories in our podcast. Stories like these:

According to the data, nowhere else has experienced the pandemic like Detroit. Episcopal priest Barry Randolph, pastor of Detroit’s Church of the Messiah confirmed that:

“Detroit is overall a poor city in general. Because of the fact that a lot of people who live here are straight across the board kind of living under the same circumstances, not everybody, but I think that's what the difference is.”

The data showed that multigenerational living among refugees and lack of public resources has made neighborhoods in Louisville, Kentucky much more susceptible to coronavirus spread. Reverend Erica Whitaker is the pastor at Buechel Park Baptist Church.

“In our neighborhood there is a lack of outdoor resources, higher crime rate, we need better safer environment, outdoor spaces, really is unsafe, people can’t go outside to escape the virus, the sidewalks aren’t safe for elderly people.”

Importantly, we also learned that even the most thorough analysis of the data doesn’t always match the lived experience of being an essential worker in Chicago:

“As we’ve gotten this data and tried to develop this story we’ve realized that there are a lot of difficult gaps that even the best data couldn’t necessarily fill for us.”

Data- It's what drives so much of national reporting on any topic. But what happens when there is no standard for reporting and analyzing it? When every state and local government is left to fend for itself to find meaningful information in the middle of a pandemic?

That's what’s happened in the U.S. over the past nine months. Data was politicized and precious time was lost as important information such as contact tracing of positive cases wasn't gathered. This unscientific approach to data led to obstacles for our data analysts and it could lead to even bigger problems in the future - more on that later.

In the face of incomplete and sometimes incompetent data, Dr. Weber was still able to give us the guidance we needed.

But it wasn’t easy, "Comparing one demographic to COVID, and doing one at a time, is not a robust way of approaching a problem and with the information we were given from different surveys, census bureau, health departments it made doing something robust more difficult and time consuming,” he said.

Right away, the analysts sent us data interpretations that solved a pressing issue for us as reporters. We had a huge geographical area to cover and limited resources to do so. We needed to know how we could responsibly cover this area without leaving out something important.

In this instance, the data was clear - the greatest impact of the virus was in the metropolitan areas of the Midwest. So we needed stories from places like Detroit, Chicago, Louisville.

We hadn’t originally planned on dedicating an entire episode to Detroit, but between what Dr. Weber found in the data and what WNIN’s Steve Burger found on the ground - Detroit had an important story to tell. One of tragedy and resilience and also, systemic failure.

“You have a city like Chicago that is totally uneven, you have the upper, lower and outright broke and poor in those cities - you have a wide microcosm of incomes - where in Detroit, it is not quite like that. There is a high concentration of poverty straight across the board in all zip codes. There is no zip code in Detroit where there are not poor people," Randolph said.

In episode six, I talk with Reverend Erica Whitaker. I sought her out because of data Dr. Weber showed me. He found that, in Louisville, there was a moderate correlation between those with no health insurance and COVID-19 infections. He also found that there was a higher occurrence of COVID cases among service workers, and he found a moderate to strong correlation between COVID infections and areas of town with non-US citizens or naturalized citizens. The zip code where all of these factors converged was 40218 - the neighborhood known as Buechel Park.

“We live in the most diverse zip code - we have a lot of refugees and immigrants, Bhutanese population. They are hard working people with some of the most at-risk jobs, sanitation, hospital and they are bringing that back into the community in which they are hovering. They all live in community and spend lots of time face-to-face. We have an older refugee population that has to bring their kids or grandkids with them to translate. We rely on a lot of community partners but some of them aren’t able to give to the community right now. We’ve had 16 members pass,” Whitaker said.

We knew from the beginning, that particular care and research needed to go into reporting on the Chicago area. If you’ve listened to episode three - you’ve heard the engaging stories of Latino essential workers in the Pilsen area.

Before our journalists got started, Dr. Weber worked with them on the data he had found, hoping to give an insight into how COVID-19 has affected the essential worker. The following discussion is an important look at the difference between gathering data from official sources and being a journalist on the ground - especially in a place like Chicago, during a time like this.

“Judith Ruiz-Branch: With our reporting out of Chicago, we initially looked at some of the data and noticed that you know, some of the things that we kind of can see on the ground like having lived here...the data didn't seem to kind of match up in our eyes and so we were curious about sort-of how certain aspects like gentrification play into data?

“Darrin Weber: Yeah, so we can, we can add anything really as long as we have the data for it. We can add anything that you're looking for. The problem with that though is the Covid data and the Covid data that may not be boiled down on that fine granular level... So the essential workers thing. I think this is probably, unfortunately, this is our most difficult one to really get an idea of what's actually happening. And the reason for that is because of the way that the Census Bureau breaks down the occupations. They don't break it down in the way that we would in COVID times where you have the essential versus non-essential.

“Karli Goldenberg: Yeah. I feel like COVID has really redefined the categories that we’re even looking into. Current ones, like I think if we could go back in time, pre-covid times and we'd ask someone you know, do you know what an essential worker is? I don't think anyone would know. I think they'd be like, what do you mean by that?”

“JRB: Like one of the factors that you initially noted, which I thought was really interesting was in terms of public transportation. You said there was surprisingly the correlation was the opposite of what you guys had anticipated going into it that actually people who took or in the areas that relied heavily on public transportation - they actually had lower cases of COVID, but I wonder if is it really that they have lower cases of COVID or is it that they're not getting tested? Because when you look at an essential worker, I think we, like for the purposes of our story, we look at essential workers as like service workers but essential workers...like the medical field also falls into essential workers. So you can have a doctor who is like in a whole different bracket economically fall into the same essential worker category as someone who works, you know, ten dollars an hour at a grocery store. So yeah, and those two people could have to take the same train to work but one of them has health insurance the other one doesn't, one of them has more readily or more access to testing and then the other one doesn't. I think going into the story...that's why we're not trying to like dissect every single like, you know data set that you're trying to like create because we know that it's very valuable and helpful and it's amazing work, but just from like the analytical standpoint of a journalist, how we're supposed to it's hard for us not to question everything because if we're going to quote like numbers and if we're going to have data, you know throughout our story. I mean we have to be really, really sure about these numbers because we risk telling an inaccurate story. It's complicated. And so in order to tell that story, you kind of have to maybe give data of the bigger picture but then say, okay now we're going to drill down and tell you like I don't know not the real story but…”

“DW: ...Like the personal stories...yeah and that's something that the data won't ever be able to highlight is those personal stories. And that's the other thing, all these numbers are estimates. There's a margin of error with each of these numbers we’re reporting.”

“JRB: So yeah, but then that's also interesting too because a lot could happen in two years in a neighborhood and then totally just trash our data. So that might be why we saw some numbers and we're like that's not right, you know?”

So, while the data led us to stories in Detroit and Louisville, it also exposed some of the shortcomings of relying solely on data to find stories.

The foundation of research from Dr. Weber and his students made us confident that our time reporting in large cities was well worth it in order to bring these original stories to you. Of course, COVID didn’t singularly affect cities - rural areas suffered too, but the accelerating factors were different. In metropolitan areas, COVID was propelled by pre-existing systemic failures. Outside of the city limits, that wasn’t always the case - more on that in episode 6.

But perhaps the most important thing that came from relying on data to bring you original reporting was not a story, but a warning.

"As a city official, as a state official, you look for plans and implementations and procedures from other states to plan, to determine what you need to do in your own city or state. If there isn't a standard way to talk about the problem, that makes talking about the solutions that much more difficult. Without having that data nationally determined, I assume that makes if very difficult for city officials to do their job effectively," Weber said.

Policy decisions ought to be based on data. But information gathered during the pandemic had no standards except those made by many, different local governments. So how will leaders, the media, historians, the public know the truth about what happened during this unprecedented time in order to take future action?

"There has to be some type of standard set. What counts as a case? What needs to be reported? We would like to see this on a state by state level but then that creates more difficulty trying to work between the states. Some type of national testing, some type of national procedure needs to be put in place so that we can get useful and effective data and be able to analyze it appropriately and be able to come to some effective and efficient solutions."

"SK: Have you seen any of that happening yet?"

"No, no I haven't. We will see what the next administration does with their coronavirus task force. It'll be interesting to see what president-elect Joe Biden puts in place, whether it is national standards and national contact tracing put in place. If that is done, that could exponentially help in analyzing and learning what happened so we can learn and go forward in the future. Undoubtedly we will face another pandemic."