It is well known that Evansville, Indiana suffered one of the first U.S. casualties in World War I. But there is an Evansville story at the end of that war of triumph, tragedy and sacrifice that has gone almost completely unnoticed...until now.

Editor’s note: Since we finished production of this story in 2018, two of the contributors to the story have died. In October, LTC Tom Orlowski, U.S. Army (Ret.), died at his home in Virginia. As president of the First Infantry Division Memorial Association, it was Tom’s efforts that enabled Chester Schulz to finally be recognized for his sacrifice in World War One. In early November, Gertrude Lant, granddaughter and namesake of Gertrude Schulz, died at the age of 96. With her passing, there is no one left with personal memory of the woman who started a national movement to assist the war effort.

According to the World War One Centennial Commission, 122,000 Americans were killed or wounded in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, the battle that brought an end to World War One in the fall of 1918. It remains the largest battle in U.S. military history.

On a monument at Wadelincourt, France honoring U.S. Army First Division casualties in one area of that massive battle, there were 215 names. Now, there are 216.

The addition is obvious and will no doubt prompt questions from future visitors. Nancy Hasting of Posey County, Indiana has been searching for the answers for nearly twenty years.

A box of letters

The journey that ended at the monument in 2018 began with a box of letters.

After her mother died in 1999, Nancy found the box in a closet at her parents’ home. Among that collection of news clippings and old photographs, what Nancy found was an unusually complete collection of letters between her great-uncle, U.S. Army Sergeant Chester Schulz of Evansville and his family.

She said, “It was a story I’d known all my life, but when I got this box of letters and started reading them and I thought, now this is pretty interesting.”

The letters provide insight into the life of an American doughboy and life on the home front in World War One. Nancy has put her family’s story into a book called, “A Tragedy of the Great War.” She also publishes a blog on WordPress called “Tracing Chester Schulz”.

“It’s not that I’m glad that those things happened, but if they hadn’t happened, he would just be another uncle to me. He’s much more real to me now, because of the letters and the story and the whole ordeal.”

Photographs and news clippings in the box also detailed the triumph of Chester’s mother, Gertrude Schulz, who was instrumental in forming a national organization of women to support the war effort.

Evansville in World War One

Like most of the country, America’s entry into World War One came as no surprise to Evansville. By April of 1917, the area had already formed infantry and artillery units for the National Guard. A cavalry company had even been proposed. Vanderburgh County historian Stan Schmitt says the Red Cross mobilized immediately and fundraising began to help finance the war.

“Basically, over the course of about a year and a half, there were five loan programs, the last one was called the Victory Loan. People pledged money to the government for the war effort. Evansville raised more than $22 million, and that’s in 1917-1918 dollars.”

Something else that began almost immediately- draft notices were sent to raise a contingent of soldiers from Indiana and Illinois.

“The Army realized real quick that they were talking about millions of men to Europe. Everybody between the right age groups, all men had to register.”

One of those notices went to 24-year old Chester Elmer Schulz of Evansville, an accountant at the Hercules Buggy Company, member of his church’s choir as well as the local Freemasons. Chester was engaged to be married to a woman named Lorena Stocking, who he affectionately referred to as “Socks”.

Chester Schulz was the youngest of four children, three boys and a girl. His father Albert was a salesman for the Indiana Stove Company. The family was comfortable financially. His mother, Gertrude Dausman Schulz, was active in the Jefferson Avenue Presbyterian Church.

"Don't worry about me"

There is no indication that Chester resented putting his life on hold for the Army. His letters home reveal a young man eager for adventure.

He wrote, “Our company is hoping not to be cheated out of a good scrap with the Hun. We are all in good spirits. Don’t worry about me, for I am in the place I want to be.”

On arriving for basic training at Camp Zachary Taylor in Louisville, Chester was assigned to the 84th Division, 335th Infantry Regiment, Company K. He was quickly promoted to corporal and then sergeant in April of the following year.

The War Mothers

Gertrude Schulz’s care for her son sparked a national movement of women supporting the troops. An account of Evansville’s role in World War One, “Sons of Men” came out shortly after the war. The author, Herman Blatt, wrote that during a visit to Chester at Camp Taylor, Gertrude had the idea to form a women’s group to support the troops.

Stan Schmitt said the idea was a popular one. “She talked to different people and the idea kind of caught on.

They set up the local War Mothers in Evansville. Little bit later, a congressman from Indiana introduced a bill in Washington to give them a national charter.”

The new group was called The War Mothers of America. Gertrude Schulz was its Acting President. Blatt noted that by the time of the first national convention, there were two million women in the U.S. who were interested in the movement.

Basic training

Army life seemed to suit Chester, despite their rigorous basic training at Camp Taylor.

A daily schedule from the archives of Camp Taylor shows that reveille called at 5:45am and the men were almost continually active until taps was sounded at 10:30 at night.

Chester wrote, “Our platoon is one of the few that has come through these hikes without losing a man. It was due to the fact that we didn’t sympathize with them when they began dragging, but instead, just urged them on and brought them all into camp. Lots of love, your kid brother, Chec.”

They received training in the use of bayonets, grenades and machine guns. They held mock hand to hand combat battles in trenches. The trench warfare would later prove almost useless in actual combat.

In September of 1918, their basic training complete, Chester and Company K boarded the troop ship Karmala at the massive military port of Hoboken, New Jersey on their way to Europe.

Chester noted an anniversary in his letter. He wrote, “Aboard transport. Dear Mother and Dad, English Channel. It was a year ago today that we pulled out of the station for our introduction to military life. We have traveled and marched many a mile since then, and are today between four and five thousand miles from home. I don’t regret being here, but can’t hardly realize I’m so far away.”

A national convention

The summer of 1918 flew by for Gertrude as she dealt with details of the War Mothers first national convention. It was to be held at the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Coliseum, finished just two years earlier as Evansville’s showcase venue.

As noted in the Evansville Courier on September 18, 1918, “They are here- the war mothers!

They have come from every part of the country to be present at the first national convention and to help in organizing the first society of its kind ever known in history.

Quite a number of the mothers arrived yesterday and each train into the city this morning will bring its load of women who have their boys overseas for the sake of democracy.”

Over two hundred delegates from twenty-two states and the District of Columbia were on hand to hear Gertrude’s opening remarks to the gathering.

“Ladies, with great pleasure I greet you and welcome you here. You, the mothers, wives, sisters and may I add the sweethearts and friends of the grandest army that has ever fought in war, have gathered from far and near to organize another army that shall stand shoulder to shoulder with that army, over there. By our united effort we can do great things, and our boys shall realize that we can fight as well as they, using our own weapons. For our God, our country, humanity and our boys, we may do anything that may become a woman.”

A highlight of the convention was a cablegram from Chester that arrived during the event saying that the Evansville troops had arrived safely overseas. The news was greeted with loud cheers.

Another message to the convention, from a little higher up, is dated the 18th. It was a telegram from

President Woodrow Wilson, thanking the group for their support of the war effort. The commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe, General John. J. Pershing, took time out a few days later to add his congratulations.

Pershing cabled, “The splendid example of patience and bravery which American mothers have set for their sons is a tremendous inspiration to the American Expeditionary Forces. In the name of these troops I thank you for a message which assures us of the courageous spirit. Pershing”

The same day that he sent that telegram to Gertrude, September 22, General Pershing formally assumed command of the Meuse-Argonne sector of northern France. It was in preparation for the offensive that would put Gertrude’s son on a cold, soggy hillside near the village of Cheveuges six weeks later.

There is a historical footnote to the convention. The most controversial topic at the first War Mothers convention turned out to be the name. While the Evansville group got their way in 1918 with the name War Mothers of America, it didn’t last long. At the group’s second national convention, held in 1919 in Baltimore, the name was changed to the Service Star Legion. The name War Mothers of America disappeared after just one year in existence.

Tracing Chester Schulz

Our search to document Chester’s experience in the American Expeditionary Force took us to France in July of 2018, along with Nancy and her sister, Ann Stevenson.

By going to France, we were able to bring context and clarity to the century-old letters and military records. It helped Nancy discover new information to update her account of her family’s story.

Our journey to trace the steps of Chester Schulz in France begins in Mussidan, a small village in southwestern France. That’s where Chester received some additional training before heading to the front lines.

Waiting for us were local museum director Ludovic Chasseigne and translator Christianne Taildeman.

Based on one of Chester’s letters, Ludovic researched village archives and found records of all the local families and businesses that housed American soldiers during the war. We might be able to find the place where Chester and his platoon stayed while they trained in Mussidan. The individual soldiers at the locations were not listed, but Chester left some clues in his letter.

He wrote, “We are billeted in the stable of an old Frenchman who has three daughters in the Red Cross and two sons in the service. He has lost one daughter. He is a fine old man and treats Schentrup and I just fine.”

With Chester’s account and the village records, Ludovic is able to narrow the possible billeting location

down to a handful of farms. According to Chester’s letter, even though they spent their days preparing for the battle, they also had time to enjoy themselves far from home in the French countryside.

He wrote, “They live on grapes, black bread, wine and mushrooms. I brought them a piece of white bread and a canteen of coffee. Their eyes got real big and they called the bread cake. Since then, they can’t do enough for us. They want Schentrup and I to drink wine with them all the time. If we drank as much wine as they wanted us to, we would be drunk all the time.”

Chester’s letter comes to life as we tour a farm on the outskirts of as in Mussidan that Chester celebrated his 26th birthday on October 6th, 1918.

Christianne translated, “The name of this small park is Seguinou. You will see that later on at the museum. There were no numbers at that time for the houses. Here the name of the owner was Durrier at that time. In Seguinou we only have three farms, three names. So, at least we know that American soldiers were billeted here.”

Chester added, in his letter from Mussidan, “There is one thing I don’t understand. They have blackberries here so thick you can’t make an impression on them. They are drying on the bushes, yet they think they are poison. Believe me, we boys sure make use of them. We have blackberries stewed and in cobblers three times a day. I took about ten of the boys out this morning and picked about six gallons in about as many minutes. They are so thick and ripe that all you have to do is hold the bucket under the bush and shake the bush.”

Nancy commented on the side trip to Southwestern France. “Mussidan is a beautiful town, for one thing. I think of this time for Chester to be such a peaceful time and a nice time. It’s great to see some of the actual places he was, actually walk in the train station where he arrived. It’s very touching to me to think this is where he was a hundred years ago. So, it’s much more real, much more exciting to me right now.”

Far from peaceful in other parts of France, battles were exacting a high cost. One of the most graphic accounts of the German strategy in the Meuse-Argonne battle was written by a lieutenant in Company M of the 28th regiment, the same regiment with which Chester would eventually serve. Maury Maverick's account appeared in the book "Doughboy War” by James Hallas.

“We had reckoned without the German rearguard action, and no doubt they had heard us telling our men to get ready. They were soldiers who had trained four years at the front. They had left their lines checkerboarded with machine guns, had left their men in the rear to fight to the death and had slowly moved out the heavy masses of troops.

Most of us who were young American officer knew little of actual warfare- we had the daring, but not the training of the old officer of the front. The Germans simply waited, then laid down a barrage of steel and fire. And the machine gunners poured it on us. Our company numbered two hundred men. Within a few minutes, about half of them were either dead or wounded.”

Desperate after suffering thousands of casualties in the summer and fall of 1918, unit commanders went looking for replacements. They found them in Mussidan.

A Proud Moment

Chester wrote in a letter, “Oct 18th, 1918. Dear Mother and Dad. I am now located with a new outfit. Our company was split to pieces to replace a part of the First Division. Green, Saunders, Schofner and I are still together. The First Division was the first to arrive in France and has gone through some of the hardest fighting. They have made a name for themselves that will go down in history. We are looking for a chance to help them maintain the name and also make a little more history of the kind they have made.”

In his next letters from France, we get a glimpse into Chester’s life as he got closer to the front. The

language is harsher, the sentences more fragmented and it’s clear the men are training hard for the upcoming battle.

On October 22, he wrote a letter as his company moved closer to the front lines. “We didn’t get time to write. We haven’t had time for a decent wash for the last week or two. After being out all day, then noncom special hikes at night, we are damned glad to hit our hay.

Started this last night, but got interrupted by a Bosch plane that decided to pay us a visit. We had to put our lights out until he was chased away. It was our first experience in an air raid. He didn’t do any damage or make a direct hit. However, he made it interesting around here. Am expecting to see some real service soon. The company is about reorganized now. I have the first platoon to take over. We have only two officers in our company, so you see it’s up to the noncoms to take the boys over.”

Marching toward the battle

Armed with military accounts of the 28th Infantry and Company K, images shot by military combat

photographers and two local experts, our group begins tracing the steps of Chester Schulz in northern France.

Richard Tucker runs a service called Tucker Tours, giving military history tours of the area around Sedan. Chris Sims retired after more than forty years with the American Battlefield Monuments Commission, the organization which maintains American cemeteries and monuments in Europe from both world wars.

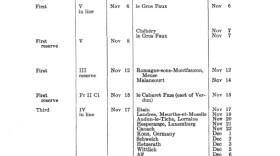

With the help of Richard and Chris, we begin tracing Chester’s steps in battle at the village of Chehery. It was there, at sunrise, accounts record that Chester and Company K took the first fire from German machine gunners. It was seven a.m. on November 7th, 1918.

Our group pauses at Chehery. Richard Tucker points out that we can see where the front line was located

just a couple of miles away on the outskirts of Sedan.

From Chehery, Chester and Company K marched up the west side of the road to Sedan, along the Bar River to the village of Cheveuges. Archive film footage of that day shows American troops under fire as they run, crouched over on the road leading into Cheveuges.

"We won because the men were willing to pay the price"

Company K, with Chester leading the First Platoon, was ordered to the northwest of the village, to attack a German machine gun position a short distance away on what was known as Hill 334. They stopped in the cover of the walled cemetery at Cheveuges to plan their attack. It was about 7:30 in the morning.

An account of the day in the history of the First Division’s 28th Regiment states that there was no artillery

support and any German positions were overcome by “the sheer force of frontal attack.”

The account goes on to say that the Germans were prepared to make a desperate stand because the loss of the hills outside Cheveuges meant the loss of Sedan and the important rail center in that city.

A quote attributed by some historians to General Pershing after the war went, “We won because the men were willing to pay the price.”

Based on historical accounts, their knowledge of military tactics and a map, we walk out toward a certain spot in that open field with Richard Tucker and Chris Sims.

Nancy Hasting is carrying a bouquet of flowers.

Richard Tucker checks the landmarks as we realize we’re close to the spot.

“I think they were about right here. They would have been near the road, so they could perhaps dash to it for cover. The Germans know they’re coming, they’re too far away when they’re down there (by the cemetery), so they would have waited until they got about right here and start shooting at them until they’d got enough of them.”

At the age of twenty-six years and thirty-one days, Sergeant Chester Schulz of Evansville, Indiana, a former accountant at the Hercules Buggy Company, member of the church choir, beloved son, brother, and fiancé, died on that hillside along with seven other Americans. It was just after eight o’clock in the morning on November 7th, 1918.

Nancy Hasting gently places the bouquet of flowers on the stubble of the harvested wheat field.

She says “I’m probably not a pretty crier.” Film producer Brick Briscoe asks Nancy if it feels like an ending to put the bouquet near the spot where her great-uncle was killed. “A little bit. Our search was to find the spot where he was killed. I’m sure it’s not the exact spot, but it’s pretty close.”

Nancy hugs her sister Ann Stevenson for a long moment and then steps back to snap images that will be quickly

attached to messages for their families back in the U.S. Unlike communication in World War One, the people waiting at home will have the information almost instantly.

Chris Sims described what would have happened on the hillside shortly after the battle.

“In Chester’s case, on 7 November, the weather was terrible. It was chilly, it was wet. Of course, the burial parties with their winter coats and heavy equipment would have slogged along as well, and hastily in a muddy field, bury the dead.”

Official accounts of the day indicate the rest of the company and other units were scattered and pinned down all day unable to advance. They were relieved and finally got a hot meal and rest on the evening of November 7th. For the surviving members of First Platoon and Company K, the war was over.

"Suspense and Sorrow"

Evansville celebrated with the rest of the nation when word came that the Armistice had been signed. In the weeks since the War Mother’s convention, Gertrude had been busy working with Chester’s fiancé Lorena Stocking and other women to raise money and shape the organization that was beginning to provide assistance to soldiers’ families, especially the families which faced financial hardship because of the war.

In her joy and relief at the news of the armistice, Gertrude dashed off a quick letter to Chester.

She wrote, on November 11, 1918, “At 3:30 this a.m., Mr. Stocking roused us from our slumber as he was returning from the Courier office. He shouted aloud, ‘The war is over! An armistice is signed!’. Dad went downstairs and woke Ray to tell him the good news, and called Lillian, all before four o’clock. But they can afford to lose some sleep with such joyful news. Now dear Chec, let us hear from you at once so we know you are safe, that our cup of joy will be filled. With loads and loads of love, a Happy Thanksgiving and a joyful Xmas. From Mother and Dad.”

Not knowing that he’d been killed in France just four days earlier, the letter was the first of several tragic miscommunications that would take place over the next few months, including some from official sources.

It was the beginning of what Gertrude would later refer to as “the suspense and sorrow” of the ordeal, and the mystery that would haunt the family for a century.

For example, in December of 1918, an article appeared in the Evansville Courier. “Chester Schulz Badly Wounded. Various rumors current about the city regarding Sergeant Chester E. Schulz, son of Mr. and Mrs. A.J. Schulz, 200 Jefferson Avenue, were quieted yesterday on the receipt of the following telegram from Washington, “Deeply regret to inform that it is officially reported that Chester E. Schulz, infantry, was severely wounded in action November 7.’

Several days ago, a local soldier wrote home and told of Sergeant Schulz having been killed in action. As Mrs. Schulz is president of the local War Mothers organization and has taken an active part in the organization since its inception, her prominence added fuel to the rumor.”

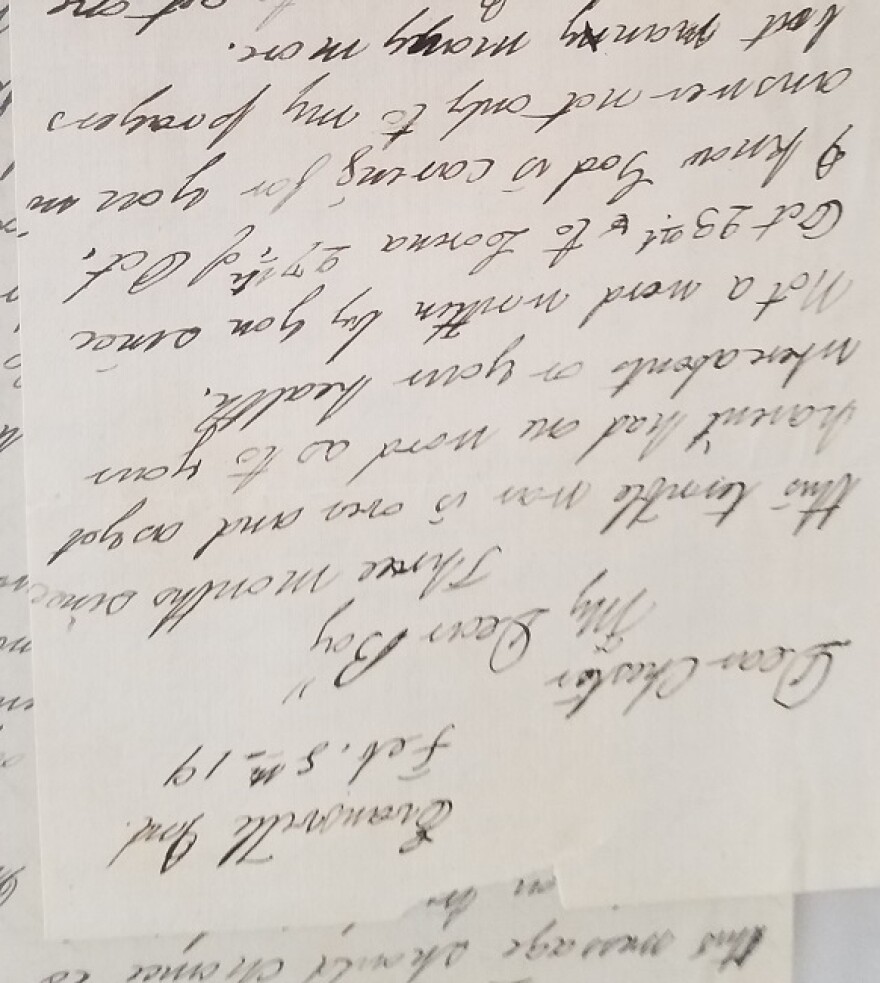

In February of 1919, Gertrude wrote, “Dear Chester, my dear boy. Three months since this terrible war

and as yet not one word from as to your whereabouts or your health. Not a word written by you since October 23rd, or to Lorena on the 27th.

I know God is caring for you in answer not only to my prayers, but many, many more. But, oh how I yearn to get one line written by you. Many of the boys are home and still coming, but none know a word about you. I’ve written to every corner of France, but no information whatever.

So, if this message should chance to reach you, try to send us a cable. I’ve asked everyone I’ve written to, but none so far. If General Pershing can help you, appeal to him. I know he’s a friend to all you boys. But hope someone, wherever you are located, will let us know.

Dad and I are holding down the old fort, or at least I am, with Nellie as my guard, as Dad has been on the road again since the first of the year. He has fine trade and is feeling pretty good. I wouldn’t leave the old fort, as I’m daily expecting to hear something from you.

Now my dear boy, I hope you’re getting along all OK, and that God will bless and keep you until you reach the shores of home. Let us hear. And with all the love that can come from a mother and father’s heart.”

Nancy said even today, that letter still has an emotional impact. “Sad. It’s still just so poignant to me a hundred years later. You can just feel it- she’s telling him, she’s wanting to hear from him. Telling him a little news from home, bringing him up to date as to all’s been happening while he’s gone. But just the, not even leaving home for four months, thinking someday somebody’s coming with word of where you are.”

Finally, in March of 1919, the family received a telegram from the War Department. An article in the Evansville Press detailed the reaction. “Son of War Mother’s Leader is Killed. In doubt for the past four months whether her son, Sergeant Chester Schulz was alive or dead, Mrs. A.J. Schulz, first president of the War Mothers of America has been writing to him weekly hoping that somewhere her son was still alive. Thursday she received official notice that he was dead.

‘The last time I saw Chester he was leading the First Platoon over the top,’ Miles Saunders, son of Minn Saunders, wrote in December. Saunders was wounded in the same battle, apparently in which Schulz was killed. And that’s the picture Mrs. Schulz has always with her now- of her son, her 'baby boy' she calls him, leading his men over the top. She said Thursday, “How many times Chester went over the top, I will never know. But I do know he went just as many times as he could, not waiting to be asked.” It was recalled Thursday that when the first official word came that Sergeant Schulz was wounded (in December of 1918), the local War Mothers organization, through a mistake of the florist, sent cut flowers to the Schulz home- symbolizing a dead son- instead of a growing plant signifying a wounded hero.”

"Letter to be opened in the event I do not return"

What happened? Why did it take four agonizing months to be notified of Chester’s death? Researching

records at the First Division Museum in Chicago, Nancy found an important clue. When replacements were hastily shoved into the First Division shortly after leaving Mussidan, Miles Saunders, Charles Schofner and Jacob Green of Evansville are listed with their new unit, but the name of Sergeant CE Schulz is never listed on Company K’s monthly roster.

The mystery was solved. At his proudest moment, leaving Mussidan as a member of the Big Red One, no one but his closest buddies knew that Chester Schulz was even there. It would take months for the Army to realize its error.

Nancy said it makes sense now that Chester’s family wasn’t notified after the battle outside Cheveuges. “When they’re checking the list, the battle’s over and the company rejoins itself and they’re checking OK, you’re here, you’re here, you’re here, there was no name for Chester and you know, he wasn’t missed. It’s a little bit ironic to me because if this hadn’t happened, if they hadn’t left his name off, it would just be another story of a death in World War One.”

In the weeks following the official notification of Chester being killed in action, more details emerged from soldiers who were with him that day.

One, from another soldier, gave an account of Chester’s death:

“Cave-in-Rock, Illinois. May 18, 1919. Dear Mrs. Schulz: I knew Sergeant Schulz while in France and I knew him for a jolly good friend as well as a soldier, and I’m sorry to have to tell you of his death.

I saw him fall on the battlefield while we were forced to push ahead. I believe he died there. Of course, I didn’t have time to get down and examine his body, but I’m sure he was dead and his corporal said his last words were, ‘I’m wounded.’ Such is life and we can do nothing more noble than give our lives for our country. Truly yours, Luther Riley.”

Like most American soldiers headed overseas, Chester had written a letter to be read if he was killed in the war. His read, “To be opened only in the event I do not return. Chester. September 18, 1917. Dear Mother and Dad: I write this to you knowing that you will fill all my wishes. I have done my bit for the country, but leave the ones behind who are all the world to me. But don’t be sad, as I feel it an honor and want you to feel the same way.

I have two insurances policies- one for $2,500 and one for $1,000. I want you to have the $2,500 policy and give Lorena the $1,000 policy as I took this out since we were engaged. I do this not because I don’t want you to have it all, but because I know Lorena’s disposition and think that she can forget by going away for a while, or anything that she sees fit.

May God’s blessings be with you all. Your son, Chester.”

The military’s Graves Registration Service was established in 1917 because U.S. officials decided that none of the families of casualties in the war would want their loved ones to be buried in Europe. They were wrong, and the chaos that ensued delayed the return of some soldiers’ remains, like those of Chester Schulz.

In April of 1919, Chester’s body was disinterred from the grave on the hillside outside Cheveuges and moved with over eight hundred other remains in outlying graves sites to a temporary cemetery a few miles away at Letanne. Chris Sims said the work of moving the bodies is difficult to describe.

“It was a very gruesome task, up to the point that many of these people who worked for the Graves Registration Service had no sense of smell or taste so that they would not have experienced, how do you say, the stench of death. And from the film footage I’ve seen, on the procedure of disinterment and the processing of remains, it seemed to me that they all became an automatism. So, no personal feelings toward the remains, they were just doing a job and one was processed and the next was in line to be processed. They had to set their emotions aside. How could one cope if you were emotionally involved with every remain that you would have to process?”

In Evansville, Gertrude Schulz had no question about where she wanted her son’s remains to be. It was clear in a letter she wrote in response to the government’s query of the families of U.S. casualties.

She wrote, “We deeply grieve over the loss of our dear son. The War Department has promised to send the remains home to those who so wished. I’m looking forward to the time when his remains will be sent to us where we have a beautiful cemetery. And my only comfort, through all the suspense and sorrow, will be to have him placed in our family lot, where we, his family, can place flowers on his grave. I feel sure my country will carry out all its promises, and return our dear one to us as soon as it can possibly be done.”

Gertrude had to deal with the final details of Chester’s return on her own. Chester’s father, A.J. Schulz, died in November of 1920.

News accounts of the funeral of Chester Schulz in April of 1921 indicate that hundreds of people turned out for a large procession. His pallbearers included the three Evansville men who transferred with him to the First Division at Mussidan. He was buried for the last time in Oak Hill Cemetery.

As Chester indicated in his final letter, his fiancé, Lorena Stocking, did go away, moving to Pittsburgh and later Chicago, but she apparently did not forget. Lorena returned to Evansville for Chester’s funeral. The woman Chester referred to as “Socks”, never married. Lorena Stocking died in 1952. There is no marker today, but records show her cremated remains were buried near her parents’ graves, also in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Gertrude Schulz’s time in the national spotlight was short-lived. The strain and heartache of the family’s ordeal affected her deeply. While she continued her public service in various ways, privately she would mourn Chester’s loss until her own death in 1929.

The only living descendant with personal memory of Gertrude Schulz is a granddaughter, another Gertrude, Gertrude Lant. Now living in a nursing home and no longer able to speak, we recorded an account in 2009. This personal story of her famous grandmother is told through the eyes of a young child.

“She was short, and fat and soft. I used to love to go there, because she had a big stuffed teddy bear.”

Gertrude Lant says she doesn’t ever remember her grandmother talking about her time in the national spotlight. But she says her grandmother and Gertrude Lant’s mother Lillian often talked of the family’s personal tragedy- the death of Sergeant Chester Schulz.

Gertrude Lant continues, “Oh yes, they talked a lot because my grandmother loved him so. She talked about how he was killed the day before the Armistice was signed. That broke her heart, to think that he was so close to coming home and didn’t quite make it. And, she used to say that poem, ‘In Flanders fields, the poppies grow, between the crosses row on row', and the tears would just roll down her face.”

A historic moment for the Big Red One

The 2018 visit was Nancy’s second trip to the First Division monument at Wadelincourt. While waiting at the monument in July, Nancy and Ann discussed the disappointing discovery Nancy made during her visit in 2014.

Chester’s name was not on the monument.

Nancy couldn’t do anything about the ordeal her family suffered because of the clerical error that caused Chester Schulz’s death notification to be withheld for several months after the war. But she decided to do something about the monument.

The owner of the Wadelincourt monument is the First Infantry Division Memorial Association. Association

president Tom Orlowski says Nancy’s request to add Chester’s name prompted a historic discussion for the board of directors.

“First of all, there’s a process. I had to ask you for the documentation that you had, and verify that through Andrew Woods at the First Division Museum. Then I had to get all that information summarized and sent out for the board (of the First Division Monuments Association) and see if they would approve that.

No one else has asked us to add a name, so it was a very rare event. They all agreed it should be done, so I had to go out and find somebody to make them (plaques). Anyone who lost his life, or her life, in defense of this country, or to advance freedom, deserves to be recognized even if it’s a hundred years ago.”

Tom Orlowski had two bronze plaques made. One went to Nancy, the other to the superintendent of the American cemetery at Romagne, who oversees the maintenance at the Wadlincourt monument. And there it sat, for several months. The superintendent couldn’t take the time to deliver the plaque to Wadlincourt, about an hour’s drive, and the caretaker at Wadelincourt didn’t want to drive to get it.

Chris Sims broke the impasse, by offering to get the plaque and bring it to Wadelincourt. As a retired employee of the American Battlefield Monuments Commission, the request was granted.

Claude Zanette has been caring for the Wadelincourt monument for the past forty years. We met him at the monument at the appointed time, ten o’clock, on July 23. We brought along the owners of the bed and breakfast, Michel Kaurin and Charlotte Leray, in hopes that a local tie would convince Zanet to agree to our request. After much discussion alongside a highway with trucks and cars whizzing by, Charlotte gave us the answer.

“He says he has the tools and he can do it right now.”

The century-long wait for recognition for Chester Schulz was nearly over.

For all the weeks and months of trying to get the plaque installed, it only took a few minutes once Claude

Zanette returned with a generator, a drill and some other tools. He and Michel made quick work of measuring, drilling, gluing and placing the screws. They were only interrupted when Nancy Hasting asked if she could make the final turns on the screws herself.

A bouquet of flowers was placed, alongside the plaque which reads, “28th Infantry, Company K, Sgt. CE Schulz.”

While the bronze plaque matches the rest of the monument, it is an obvious addition. It’s easy to imagine that future visitors will reach for a wireless device to check the name. I asked Nancy Hasting what she would say to them.

“I would tell them it’s there to honor a forgotten soldier, who should have been up there with his Company K mates, and when it wasn’t there, that we care enough a hundred years later to see that he gets the recognition he deserves…that we never forget.”