Lloyd "Lucky" Hall (at far right) died of Covid-19 in March 2020 at age 69. He leaves behind a wife and a family of children and grandchildren. (Photo courtesy Sirrea Whittaker)

Sirrea Whittaker describes her dad as the life of the party, an outspoken Black man with a love for his Omega Psi Phi fraternity and a sprawling network of friends.

“And it sometimes was annoying, because like, you can go to the grocery store and you leave two hours later because he finds someone he knew,” says the 36-year-old working mother from Indianapolis.

His 5-year-old granddaughter describes him a little differently: "He was the man that gave me chocolate milk every night, when we spent the night."

Last March, Whittaker’s father, Lloyd “Lucky” Hall, died from COVID-19 after being admitted to an Indianapolis hospital. He was 69.

Whittaker says that before COVID-19 hit, he was full of energy and in good health. “I think the main thing that would have classified him as high risk was the fact that he was an older African American male.”

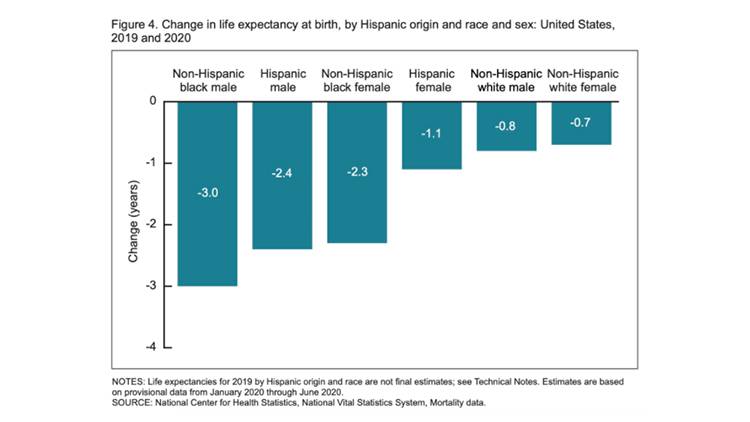

A recent CDC report shows that the pandemic decreased the life expectancy of a typical American by a full year. And it seems that Black Americans have been affected the most.

Preliminary data in the report looked at death certificates from January to June of 2020. Over that period, life expectancy was 77.8 years — down from 78.8 years in 2019.

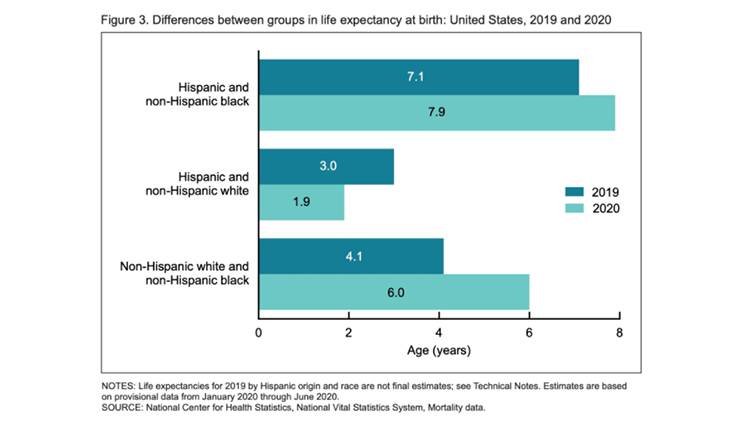

“The report definitely shows us that life expectancy for Hispanics and for non-hispanic Blacks went down more dramatically than in non-Hispanic white populations,” says Brian Dixon, director of public health informatics at the Regenstrief Institute in Indianapolis.

Dixon cautions that the data is provisional and might change when the year-end report comes out. But the disparities are likely to stand.

The report shows that while Black Americans live to age 72, whites live to 78. That six-year gap is the widest since 1998.

Dixon says the gap results from a complex web of socioeconomic and health disparities that Black Americans face — literally from cradle to grave. They face higher rates of infant mortality as well as higher levels of chronic conditions like cancer, diabetes and heart disease.

Ronald Rice Jr. is a community networker for the northwest side of Indianapolis. He works on projects to improve quality of life in predominantly Black neighborhoods.

He says stress is another major factor. Doing things that are good for your long-term health is just not pertinent when you’re constantly in survival mode — like many in the city's Black community.

“The thing is, that's the least of my worries," he says. "I'm so tired from, you know, working, you know, eight-plus hours every day, or having to do overtime, just to be able to have money to feel like my job is actually worth it.”

He describes it as trying to live the American dream — but with fewer options than everyone else.

“And again, a lot of those options. Yes, they were taken away from us when they red-lined us ... you know. the systemic racism,” he says, referring to a government policy that limited bank loans in many Black communities across the U.S.

Such racial inequality has run deep for more than 100 years, says Elizabeth Wrigley-Field, a University of Minnesota sociologist studying the history of infectious diseases.

She says it’s important to keep death tolls in perspective. To illustrate this deep-rooted, “extreme inequality,” she points to the 1918 flu pandemic.

“White mortality during the 1918 pandemic ... was such a big spike, it was almost off the charts." she says. "But white mortality during that pandemic was less than black mortality had been every single prior year.

“And actually, that's still true today. White mortality during the COVID pandemic in 2020 will probably be less in the final accounting than Black mortality has ever been in the United States."

Today, COVID vaccines are slowly getting the pandemic under control and moving Americans closer to some sort of normalcy.

But Whittaker says this disparity will continue and needs to be addressed. She also believes that those lost to COVID must be honored.

“You don't want to say goodbye. You don't want to be like, ‘Dad, is this my last phone call?’” she says while fighting off tears. “Sometimes I wish I had asked that question."

This story was produced by Side Effects Public Media, a news collaborative covering public health. It is part of a partnership between Side Effects Public Media and The Indianapolis Recorder.